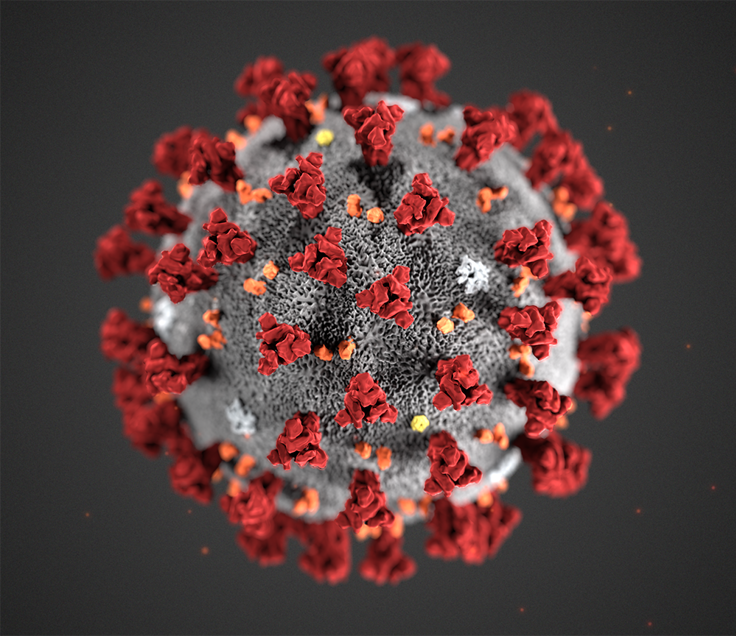

Facts about the SARS-CoV-2 virus and COVID-19 disease

Last update

This content is archived and will not be updated.

The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus was discovered in January 2020. New knowledge about the outbreak, the disease and risks will be regularly updated.

About the virus

The coronavirus family includes many different viruses that can cause respiratory infection. Many coronaviruses only cause colds, while others can cause more serious illness and in some cases, death.

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 was first discovered in January 2020. It has some genetic similarities to the SARS virus (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) which also belongs to the coronavirus family. The virus that causes MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) is another coronavirus.

Coronaviruses are also detected in animals. In rare cases, these coronaviruses can develop so they can transmit from animals to humans and between humans, as seen during the SARS epidemic in 2002. The SARS virus infection probably came from bats via civet cats and other animals. Dromedaries and camels were the source of infection for the MERS virus discovered in 2012.

SARS-CoV-2 is believed to come from bats and was transmitted to humans in the end of 2019, either directly or via other animals.

Different variants of SARS-CoV-2

As with other viruses, there are small changes in the genetic material (RNA) of SARS-CoV-2 as it multiplies. These are called mutations. Most mutations have little or no effect on the properties of the virus, but occasionally mutations occur that lead to changes that may affect the virus' infectivity, ability to cause severe disease in the host and ability to escape the immune system after vaccination or having had the disease (immune escape).

These variants are closely monitored as they may have an impact on the development of the pandemic. So far, several variants of SARS-CoV-2 have been identified that are monitored internationally. These are called VOC (Variants of Concern) and VOI (Variants of Interest). See an overview of these on the pages of the European Centre for Disease Control, ECDC. NIPH closely monitors the development of these variants and updated information can be found in our risk assessments and in our advice on the detection and monitoring of these variants.

All vaccines that are approved in Norway provide good protection against severe disease progression in all the currently known virus variants, including those identified as VOC and VOI.

Modes of transmission

Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 mainly occurs during close contact with an infected person by exposure to small and large droplets containing viruses from the respiratory tract. People with COVID-19 are most contagious for 1-2 days before the onset of symptoms (pre-symptomatic period) and in the first days after the onset of symptoms. Someone can be infected with SARS-CoV-2 without developing the disease (asymptomatic), yet still be contagious. People who do not develop symptoms are likely to be contagious to a lesser extent than those who develop symptoms.

Traditionally, modes of transmission of respiratory tract diseases have been divided into three categories: contact transmission, droplet transmission and airborne transmission. In recent years and during the ongoing pandemic, a lot of research has been carried out, not least the spatial transmission of droplets of various sizes from the respiratory tract. Much has also been learnt about how SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted. What has been defined as droplet transmission and airborne transmission overlap more than previously described. Two important factors that are important for transmission are droplet size and distance to the source of infection. Instead of defining something as droplet transmission or airborne transmission, the European and American centres for disease control (ECDC and US CDC) have begun to describe the modes of transmission of respiratory tract diseases in three categories:

- Inhalation of small and medium-sized droplets containing infectious virus. The risk of transmission is greatest near a carrier, where the concentration of the droplets is greatest.

- Deposition of large and medium-sized droplets of virus onto exposed mucous membranes, such as droplets from coughing and sneezing that hit the eyes or mouth. The risk of transmission is greatest near an infected person.

- Contact transmission: touching mucous membranes (eyes, mouth, nose) with virus particles from unclean hands, for example after contact with surfaces contaminated with viruses, direct contact with the carrier, or deposition of viruses on hands.

People with SARS-CoV-2 infection can emit droplets of virus from the mouth and nose. The degree of droplet formation from a person depends on both the individual and the activity. Sneezing, coughing, shouting, singing and exercising increase droplet formation. In addition, there are individuals who, for unknown reasons, produce more droplets than others (10-100 times more). The amount of virus in each droplet can also vary throughout the disease course and between individuals.

The concentration of droplets decreases with increasing distance from the source as large droplets quickly fall to the ground, and the concentration of the smaller droplets is diluted in the air. Current knowledge suggests that SARS-CoV-2 is mainly transmitted by inhalation and deposition of droplets with close contact. Small droplets can remain suspended in the air for a long time (minutes to hours) and move further than larger droplets. Although the general risk of transmission decreases with increasing distance, transmission over longer distances can occur by the spread of virus-containing droplets from the nose and mouth of an infected person. The risk of transmission with small droplets over longer distances increases with increasing time spent in rooms with a low air volume or insufficient ventilation, and in connection with activities that increase droplet formation. Mass virus transmission episodes have occurred after indoor gatherings with a high person density and activities that increase droplet formation, such as singing. The risk of transmission in general, and of mass virus transmission episodes, seems to be much lower outdoors.

Contact transmission can occur either through direct contact with a contagious person (e.g., hugging and shaking hands) or indirectly via contact with other surfaces that have been contaminated with viruses (e.g., door handles, light switches or payment terminals). Drops of infectious virus can therefore be transmitted from the respiratory tract to surfaces that become contaminated and onto the mucous membranes of the nose, mouth and eyes of a susceptible person.

Laboratory studies suggest that SARS-CoV-2 can survive on surfaces from a few hours to several days, depending on the amount of virus, type of surface, temperature, sunlight and humidity. However, the presence of live viruses on different surfaces is not the same as their ability to cause infection in humans.

It is unknown what proportion of COVID-19 patients are infected via the various modes of transmission, and in many of the studies performed, it is also difficult to distinguish between the various modes of transmission with certainty. Recent knowledge indicates that inhalation from a short distance is the most important mode of transmission. It has also been shown that inhaled transmission over distances of more than two metres can occur under certain conditions.

Although contact transmission is probable in some cases, it is still unclear how important this mode of transmission is for SARS-CoV-2. The virus has been detected in faeces, blood and urine, but so far it is not known that anyone has been infected by contact with these body fluids.

Even with a different division of modes of transmission and increased knowledge that inhalation transmission can occur over distances of more than two metres, we do not currently recommend a change in current routines and infection control measures in the population or for the health service, including the laboratory service. We will continue to recommend stricter measures for indoor than outdoor activities. Experience from Norway shows that the infection control advice has worked well to limit transmission of SARS-CoV-2 when routines have been followed (including the use of personal protective equipment) in hospitals and other healthcare institutions.

Infection from food, water and animals

Currently, there are no known cases of infection via food produced in Norway or imported, or from water and animals. Several systematic reviews have concluded that this is an unlikely mode of transmission.

There have been some cases of transmission between animals and humans. Mink and other species in the marten family appear to be highly susceptible to infection, and both human-to-mink and mink-to-human infections have occurred in the Netherlands and Denmark. It is important that people with COVID-19 or people in quarantine do not go to work as keepers and have close contact with mink.

Infection from animals does not appear to play a role in transmission of the virus.

- Mattilsynets informasjon om covid-19 og dyr (Norwegian Food Safety Authority)

- OPINION of the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety (systematic review from ANSES OPINION)

- ICMSF opinion on SARS-CoV-2 and its relationship to food safety (systematic review from International Comission on Microbiological Specifications for Foods)

- Questions and Answers on the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) (World Organisation for Animal Health)

In the case of swimming pools, the chlorine content of the pool water will be sufficient to inactivate coronaviruses and other viruses. However, physical contact in changing rooms and by the pool could lead to transmission as with any other close contact.

How contagious is it?

Calculations estimate that a person infected with coronavirus infects 2-3 others whereas a person with influenza will infect 1-2 people. Probably fewer than 20 per cent of those infected with SARS-CoV-2 virus account for 80 per cent of the transmission. This indicates that the majority of confirmed cases will not transmit further, while a minority will infect many.

The number will probably be lower than 2-3 in Norway because we have a lower population density and have implemented infection control measures.

Incubation

The incubation time (from infection until symptoms appear) is usually 4-5 days. Based on current figures, 98 - 99.9 % of infected people develop symptoms within 10 days, but a few will develop symptoms later.

Symptoms and disease

COVID-19 can cause anything from no symptoms to a severe disease course. In rare cases, it can be fatal. Common symptoms of COVID-19 are respiratory tract symptoms and more general symptoms such as malaise, fever and muscle aches.

The symptoms appear to differ with the virus variants. With the omicron variant, now dominant in Norway, the most commonly reported symptoms are runny nose, headache, lethargy / lack of energy, sneezing and sore throat. Sore throat and runny nose appear to occur more frequently with the omicron variant than the delta variant. Other common symptoms are cough, hoarseness and fever. Loss of sense of smell and taste seems to be less common with the omicron variant than the delta variant. An overview of the frequency of symptoms from the two virus variants is shown in the table below. Other symptoms may also occur, alone or in combination with others, such as abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhoea, and confusion. Children and the elderly in particular may have atypical symptoms. To date, there is little research into the differences in symptoms between vaccinated and unvaccinated people with the omicron variant.

The symptoms that occur with COVID-19 are the same as with a number of other respiratory tract infections. It is therefore not possible to distinguish COVID-19 from other respiratory tract infections based on symptoms alone.

| Symptom | Omicron | Delta |

Runny nose | Common | Common |

Headache | Common | Common |

Lethargy/lack of energy | Common | Common |

Sneezing | Common | Sometimes |

Sore throat | Common | Common |

Persistent cough | Sometimes | Common |

Fever | Sometimes | Sometimes |

Loss of sense of smell | Rarely | Sometimes |

Shortness of breath | Rarely | Sometimes |

Adapted from The ZOE COVID Study (COVID.joinzoe.com)

Many people who are infected with SARS-CoV-2 do not develop symptoms. Studies that have examined previous virus variants have shown that about 20-40 per cent of those infected had no symptoms. Corresponding figures for the omicron variant are currently uncertain, but are assumed to be higher.

The omicron variant is more contagious than previous virus variants. This also applies to those who have been fully vaccinated. However, vaccinated people are still better protected against infection than unvaccinated people, and they have a significantly lower risk of being admitted to hospital with COVID-19 and of needing intensive treatment. Mortality is also lower.

The omicron variant appears to cause a less severe disease course than the delta variant among all age groups. The risk of being admitted to hospital is significantly reduced, the risk of needing intensive care is reduced and the length of stay in hospital is reduced. Admission to hospital is most common among the elderly and people with underlying diseases.